We arrived home from the East Coast on June 23, spent two days getting the RV cleaned-up and in storage, but it would only be there a couple days. Starting the 1st of July, we’d have the grandkids for a week, and would be headed off for Birch Lake, near Barnsdall, OK (NNW of Tulsa). Barnsdall is best known for having been the home of both Clark Gable and Anita Bryant, and also the only town in the world with an oil well right in the middle of Main Street.

An oil well smack in the middle of Main Street.

The trip east from NW Oklahoma is interesting in how the landscape changes. The NW parts of the state are dry, parched. The colors are of the brown vegetation and red dirt. Once you pass Ponca City in the Northern part of the State, the scenery quickly takes on a much more interesting and attractive appearance. There are honest-to-goodness trees, lots of them. Since the Eastern part of the state gets a lot more rain, everything becomes green. The horizon is no longer a straight line, but is filled with rolling ridges and hills, and the road follows the contours making the ride much more interesting.

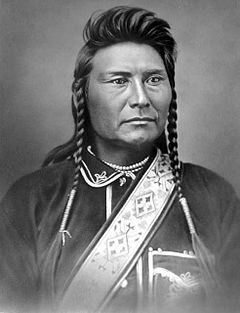

Credit: Wikipedia

Chief Joseph

Just before Ponca City, one passes Tonkawa, an area that played an important role in the story of Chief Joseph and the Nez Perce tribe. Most people have at least a passing knowledge of the story of Chief Joseph, but if you want a better understanding, here are a few books on him and his people.

Chief Joseph and the Flight of the Nez Perce: The Untold Story of an American Tragedy by Kent Nerburn, 419pp.

Nez Perce Chief Joseph by William R. Sanford, 48pp.

Chief Joseph and the Nez Perces by Robert Alan Scott, 144pp.

I Will Fight No More Forever: Chief Joseph and the Nez Perce War by Merrill D. Beal, 366pp.

The last title refers to the words Chief Joseph uttered before surrendering to Army Col. Nelson A. Miles. “Hear me my chiefs. I am tired. My heart is sick and sad. From where the sun now stands, I will fight no more forever.” The chief surrendered to save the lives of the imprisoned women and children of his tribe. Chief Joseph and his people would thus begin an eight-year exile from their homelands in Idaho. In an ironic twist of fate, the Western expansionism that was displacing the tribe from their homelands was promoted by the Nez Perce themselves. The Lewis and Clark expedition would have failed, and everyone on the expedition would have died and disappeared from history except for the intervention of the tribe. In 1805 the Nez Perce found Lewis and Clark and the Corps of Discovery sick and starving, and fed them and nursed them back to health. Now in this turn of fate, Chief Joseph and the Nez Perce, refusing to be herded like cattle and relocated onto a reservation, fled north in an effort to reach Canada and evade U. S. Army authority. With only 250 warriors, Joseph held the Army at bay during a chase that went 1,700 miles and lasted 15 weeks. During the course of the pursuit, there were at least a dozen encounters with Army forces that kept trying to push them south. They were finally forced to surrender at Bear Paw Mountain, Montana, just 30 miles short of the Canadian border. Still, his courage and cunning had Chief Joseph being called the “red Napoleon.”

The Nez Perce were moved to Fort Leavenworth, Kansas, in November , 1877. The following year the tribe was moved again, this time to the Quapaw Indian agency at Baxter Springs, KS. In 1879 they would be uprooted and moved a third time, then to the Oakland Reservation in the Indian Territories, the site of present-day Tonkawa. The Nez Perce made a serious effort to become economically self-sufficient there. They even established a day school that attracted both adults and children. However, they could not become acclimated to the harsh environment, and the death rate was abnormally high.

Continued petitions before Congress for their repatriation finally bore some fruit in May, 1884. The bill became law on July 4th, however the tribe was to be moved not to their homelands along the Clearwater River, at Lapwai, Idaho, but instead to another reservation, the Colville Reservation, in Northern Washington. Chief Joseph and his people objected to the move, saying they had been “punished enough and would not voluntarily consent to further humiliation.” Before boarding a train on May 22, 1885, four Nez Perce chiefs were required to sign a document relinquishing any claims to the Oakland Reservation.

During their stay at Tonkawa, from 1879 to 1885, over 100 Nez Perce children had died of malaria and other diseases, including Chief Joseph’s daughter. Also buried here is Halahtookit, the son of William Clark and a Nez Perce woman. Before departing, Chief Joseph had the burial ground enclosed by a log barrier so that the graves might be preserved. In Nez Perce, Tonkawa means “They all stand together.”

No comments:

Post a Comment